Leonardo DaVinci

By Bruce Shawkey

I found a source on the Internet that shows several pages for free. The address is here:

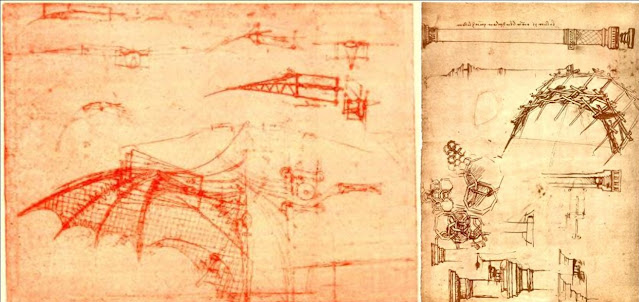

Here are a few images from the notebook.

A recent article on the Internet featured the book, "How to Think Like Leonardo DaVinci," a book which I have in my library. Here's what the author of that article said:

When I turned forty a couple of years ago, one of the things I did for that milestone was to go through all the journals I’ve kept from childhood through adulthood. It was a way to do a retrospective inventory at the midpoint of life.

In one of my journals from high school, I had pages of notes from a book I had completely forgotten about but which had a big impact on me during those formative years: How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day by Michael J. Gelb.

The book uses the life of Leonardo da Vinci as inspiration for habits that can enhance your thinking, unlock creativity, and create a flourishing life.

I picked up a copy to re-read it as a middle-aged man, curious whether the book would still inspire and motivate me the way it had when I was a teenager. And to my pleasant surprise, it did!

How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci is a really fun read that mixes history and self-improvement and combines philosophical ideas with concrete practices that can be incorporated into your life.

Below, I highlight the “Seven Da Vincian Principles” Gelb lays out in the book, along with some corresponding exercises that both 17- and 42-year-old Brett found useful.

Curiosità – Cultivating Curiosity

Leonardo never stopped asking questions throughout his life.

Unfortunately, as we get older, we tend to get less curious. We often accept what we know as sufficient and stop exploring the unknown.

To cultivate the principle of Curiosità, Gelb recommends that you:

Keep a notebook. Leonardo always kept a notebook with him. He filled thousands of pages with observations, sketches, and questions. Do likewise. Write about anything that catches your attention in your notebook. Doodle in it. Capture ideas. Write down questions. How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci inspired me to keep a pocket notebook on me at all times throughout high school and into my adult life.

Make a list of 100 questions. Write out 100 questions. They can be about anything and everything — whatever you wonder about. Make the list in one sitting. Write quickly, and don’t overthink. This exercise reveals themes or topics that are important to you.

I did this exercise in my teenage journal; here are a few of the questions I wrote down:

What will I be like in 10 years?

Where will I live when I’m older?

What is the measure of a man?

Am I reaching that measure?

Is technology the downfall of society?

17-year-old Brett was deep, man!

2. Dimostrazione – Testing Knowledge Through Experience

Leonardo sometimes referred to himself as a discepolo della esperienza — a “disciple of experience.” He didn’t just take other people’s word for things; he experimented, tested, and observed for himself.

To develop Dimostrazione: Inventory the origin of your beliefs. Make a list of three beliefs and mental models that guide your navigation of life. After you’ve made your list, examine each belief and consider the degree to which the following sources have influenced them: media, other people, and your own experience.

3. Sensazione – Sharpening Your Senses

What made Leonardo such an amazing artist was his keen observation skills and ability to fully immerse himself in the sensory details of the world around him. Here are a few Leonardo-inspired sense-sharpening practices:

Describe a sunset. Find a quiet place outside at dusk to observe the sunset. Write down a detailed description of the experience.

Learn to draw. For Leonardo, drawing was a foundational skill for understanding the world. His notebooks are filled with sketches. You don’t have to be an expert artist like Leonardo, but learning how to draw can be a powerful tool for acquiring knowledge. It can help make abstract ideas concrete. After my conversation with Roland Allen about Leonardo’s notebooks, I was inspired to learn how to sketch. Progress is slow, but I’m improving!

4. Sfumato – Embracing Uncertainty

One of Leonardo’s greatest strengths was his ability to be comfortable with ambiguity. The Mona Lisa is a perfect example of this. The word sfumato (which means “smoky” in Italian) describes Leonardo’s painting technique of blending edges, but for Gelb it also reflects his ability to navigate uncertainty and the tension inherent therein.

To develop the principle of Sfumato, cultivate “confusion endurance.” Contemplate paradoxes in life such as Joy and Sorrow — Think of the saddest moments of your life. Which moments were most joyful? What is the relationship between these states? Strength and Weakness — List your strengths and weaknesses. How are these qualities related?

5. Arte/Scienza – Balancing Art and Science

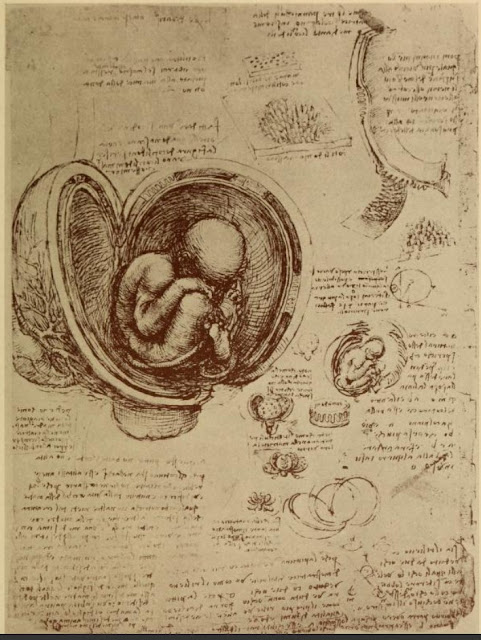

Leonardo seamlessly blended science and art. His anatomical drawings are both scientifically accurate and aesthetically stunning. He saw no divide between logic and creativity.

To cultivate arte/scienza, practice mind mapping. Inspired by Leonardo’s habit of nonlinear note-taking, mind maps use images and words to connect ideas organically. In your notebook, mind map questions like: What do I want to accomplish in the next 5 years? What should my next article/podcast/project be about? What do I know (or need to know) about [topic]?

What steps do I need to take to reach this goal?

What should I include in my trip/event plan?

What areas of my life need more attention right now?

What are the root causes of this issue?

What are possible solutions to this problem?

What are the pros and cons of my two options for this decision?

What criteria should I use to make this decision?

What are the short- and long-term consequences of each choice?

6. Corporalità – Physical Fitness and Poise

Leonardo didn’t just exercise his mind — he took care of his body, too. He was known for his strength, endurance, and grace. According to sources, Leonardo was able to bend a horseshoe with his bare hands. He combined brains and brawn! To cultivate Corporalità yourself, you can practice the many habits that promote physical health and poise, like taking a morning walk, strength training, eating a balanced diet, and improving your posture.

7. Cultivate ambidexterity. Leonardo was naturally left-handed but also developed his ability to work with his right hand. Spend the day doing your usual tasks like writing and brushing your teeth with your non-dominant hand.

I enjoyed re-visiting How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci. It’s inspired me to renew some practices from the book that I did as a high schooler. I’m feeling a bit more creative already. It’s also just been fun.

If you want to cultivate a more curious, creative, and well-rounded mind and become a real Renaissance man, try some of the exercises above and get writing, thinking, asking, and drawing.

-----------------------------------------

I practice many of these things, but where I falter is Corporalità – Physical Fitness. I need to get in better shape for this upcoming Amtrak vacation with Dawn.

Here are more images from Leonado's notebooks:

Other tidbits:

Early years

In a tax return filed in 1457, Antonio di Ser Piero claimed Leonardo as a member of his household. Little else is known of Leonardo's early life, but several facts support the theory that he grew up on a hillside farm under the care of his mother, Caterina, wife of Achattabrigha di Piero del Vaccha da Vinci, a maker of brick and pottery kilns. Here the boy could strengthen body and mind exploring the marshes and lakes of the valley and climbing the mountains behind his home. Here he would have become acquainted with its many medicinal herbs and with the ochre that was mined for medicines as well as for pigment.

From a book by Emily Hahn

When you go to Florence, Italy, and look at the city and the rocky, hilly country around it. you may think that all of this has changed very little since the great palaces and bridges were first built. And you will be right. Those bare or olive-covered hills of Tuscany and the long empty valleys between the hill ranges are just the same. And those castles and walls, those bell towers in the distance, are not very different from the scenes the Italians looked upon five hundred years ago. The city itself would not seem strange today to Leonardo da Vinci who lived there long ago. Of course he would notice that the old city walls have broken down and a number of houses have sprung up beyond.

He would recognize the Pitti Palace, and the Medici tomb, and the workshops of the goldsmiths. He would remember the bridges and the golden glow of the stone itself. For the stone of which many of these houses are built seems, through the centuries, to have soaked in something of the hot sun of Florentine summers. Leonardo was born in 1452 near Vinci, a village not far from Florence. He was about the same age as Christopher Columbus. If you think of them as if they belong together, you will not be wrong. They belong to the same age and shared the spirit of that age—the spirit of exploration, curiosity and desire for truth.

A stranger to our civilization might wonder why we pay such tribute to Leonardo da Vinci. He might very well ask us to show what this man has done to make us talk of him with such admiration. I imagine that he would say, "I can understand your reverence for Columbus. He discovered the New World.

I can see why you would make a fuss about Michelangelo—there are all his statues and pictures as proof of his genius. Or Botticelli, or any of the other artists of the time. I can understand why you remember Luther, who was soon to stir up a revolt in Germany against the great Church. I can see why you would remember villains like the Borgias. All these fifteenth-century people did something. or left something, to prove how they affected the world. "But what did Leonardo leave behind that explains all this excitement over his name? From what I can make out, he left precious little: few paintings, or bits of painting in other people's compositions—a few pieces of sculpture—evidence that he planned a great statue, but never finished it—a number of little notebooks of scribbles and sketches. That's all. Why do you honor the name of Leonardo da Vinci?"

If you look at it that way, the stranger's question is hard to answer. But the fact is, we do remember Leonardo. We do honor him for what he was, and we think of him as a greater man even than Botticelli. The world has always known he was a great man, even before his famous notebooks were gathered up and studied. His reputation began during his lifetime and has never died out, though it has had its ups and downs. The remarkable thing about Leonardo was that he was interested in everything. Centuries before anyone else had even started to guess about many subjects. Leonardo seems to have known a good deal about them.

Of course he was a great painter as well. But he didn't leave enough of his work to prove it to those who demand quantity as well as quality. He was a very good-looking man; people who knew him said he was "the most beautiful man who ever lived." But he had no famous love affairs; he never married or had any family. Unlike so many heroes that we love to read about in America, he didn't illustrate a great success story against tremendous odds. In his lifetime he didn't have the honor he deserved. No, those ordinary romantic stories have nothing to do with Leonardo. He was great purely because of his tremendous intellect. It was his brain that created the adventure of his life, and that adventure is still exciting today, five centuries later.

Leonardo's father was Piero da Vinci, meaning "of the village of Vinci." He was a young lawyer, son of a long line of lawyers. Leonardo was nurtured and taught as well as any boy in the village. But it is probable that the local school was quite mediocre even though Vinci was near Florence and the new enthusiasm for learning had spread out a long way. Leonardo's father was a clever and capable lawyer, and there was much coming and going in the family between Vinci and Florence. But the boy Leonardo wasn't a quiet, well-behaved pupil. He neglected Latin and mathematics and literature. Indeed, he seems to have preferred finding things out in his own way, at his own speed. Frequently he would slip away to climb the rocky mountains that surrounded his home. There he would gather fish and other small animals and watch the way the rivers ran. One day, as he was to remember later, he stood for a long time staring at a layer of rock that he came across, high up in a cave in the wind-swept hills. There were shells embedded in that rock, shells he recognized as belonging to some sort of sea creature, and the bones of a big fish.

Now the sea shells and bones had turned to stone, or fossils, as we call them. How had they got there, miles away from the sea and hundreds of feet above sea level? Because they were part of the rock and embedded in it, Leonardo knew no person could have brought them all that way and left them to puzzle other people. Today we know the answer to that puzzle. That is not because we are cleverer than the people of Leonardo's day. It is because scientists have had five hundred years longer in which to observe and experiment. But nobody could explain to Leonardo about sea shells on a mountain because no one knew. Furthermore, not very many people even wondered why sea bones should be found in a mountain cave. But Leonardo had a thirsty curiosity that noticed things like that and a quick brain that tried to work out the answers. That is why he was so remarkable a person. He had a modern brain, yet through some freak of chance he was born way back in I452. Probably you have heard of the Renaissance, which means "re-birth" or "renewal," as an important period in European history. It is hard to name any particular dates for the Renaissance because it happened to different countries at slightly different times, spreading slowly through the continent of Europe. We know, however, that Leonardo was born right in the middle of the Italian Renaissance. He is so much a part of it that it is sometimes hard to decide whether Leonardo's genius flourished as a result of the influence of the age, or whether he gave the Renaissance a push by being the way he was. Probably both are true.

Certainly we know that an extraordinary number of important things happened in Leonardo's time. For example, printing with movable type was invented just two years after his birth. Paper was invented, too, or at least rediscovered, at this time. You can imagine what a difference paper and printing would make to a civilization which had depended on parchment and hand-writing for its books.

All of a sudden books became comparatively cheap and plentiful. And those people who led the way in new thought were able to record their ideas for hundreds of others to read. With printed hooks, more and more people could learn about these new ideas. While Leonardo was a young man, Copernicus was born—Copernicus, who studied the theories of the ancients and finally published his conclusion that the world was round like a ball and moved around the sun. We know that Columbus, too, believed this. In fact, many learned men did. There were countless other investigations and theories springing up all around. Leonardo's interest in those fossils was a typical example. Probably his grandfather would not have bothered about them. There they were, he may have thought if he thought anything. How they got there would probably not have interested men of that generation. But in Leonardo's world the very air was different; it made people want to think. Science came into its own. One of the things it seemed natural for Leonardo to try to do was paint. Nowadays it is hard for us to realize how important the arts of painting and sculpture seemed to men and women of fifteenth-century Italy. Then, drawings and paintings and sculpture not only gave pleasure to the world, but were actually necessary, for there were no cameras or photographs. The only way to record the faces of famous people or the important events of history was to paint or draw or model them.

Leonardo worked hard at his drawing. He made sketches and notes of the flowers and birds and rocks and fish that caught his eye. He was passionately interested in painting, not only in getting a scene down on canvas, but in discovering some new and better way to mix his paints. For in Leonardo's day, a good Florentine artist was responsible for the manufacture of his materials.

One of the most exciting discoveries of the Renaissance was made in the field of art. For it was at this time that artists learned what we call the rules of perspective. Until then, pictures had been drawn or painted as a child makes pictures. Artists had ignored the fact, obvious to us, that objects seen at a distance are small, and those close up seem large. Without any hesitation they painted scenes in which angels hung in the clouds like giants, as large in the distance as the saints on the ground close to the viewer's eye.

But during the Renaissance artists began to realize that two parallel lines stretching out into the distance look as if they were coming together. They began to play with the new fashion, pointing out jubilantly to each other that with careful application of the rules of perspective they could play any number of tricks. They could make their pictures look much more real.

They caught the trick of using light and shade to make rich velvet gleam on the picture as it really did in the hand. They learned to cause the limbs and face of some figure to appear as if they actually stood out on the canvas. Perspective was a wonderful new toy. In the great studios of Florence it was the chief topic of conversation among artists and their apprentices. At home in Vinci, young Leonardo also experimented and played the new game of perspective. He was a tall, beautiful, fair-haired boy, about thirteen years old, when one day his skill tempted him to try something harder.

Comments

Post a Comment